In Advance of the Broken Arm (1915/1968)

The original In Advance of the Broken Arm was a 1915 sculpture by Marcel Duchamp. A readymade, the work consisted of a snow shovel hung from the ceiling of a gallery. I used the past tense there in order to maintain the illusion that this text is a perfect copy of text found elsewhere on this site. This illusion is now broken, or at the very least warped.

Recreations of Duchamp's In Advance Of The Broken Arm are on display in museums in New York, Stockholm and Milan. Thinking about these careful replications of an absent absurdity makes me laugh. Thinking about how a shovel and a broken arm might relate to each other makes me laugh, even if thinking about shovelling snow with my torn rotator cuff makes me want to cry instead.

Thinking about The Fountain, Duchamp's most famous work, makes me laugh; there's something "funny" in multiple senses about the fact that even its authorship, so important to the sense of the piece, is contested.

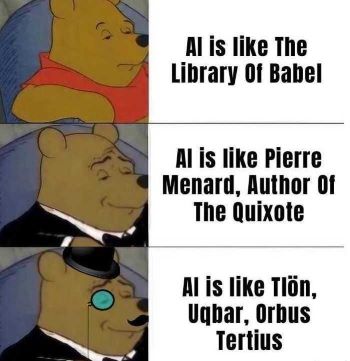

I've spent most of my adult life thinking about J.L. Borges' short story Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, but I don't think I've ever thought of it as often as I do now.

From the remote depths of the corridor, the mirror spied upon us. We discovered (such a discovery is inevitable in the late hours of the night) that mirrors have something monstrous about them. Then Bioy Casares recalled that one of the heresiarchs of Uqbar had declared that mirrors and copulation are abominable, because they increase the number of men. I asked him the origin of this memorable observation and he answered that it was reproduced in The Anglo-American Cyclopaedia, in its article on Uqbar. The house (which we had rented furnished) had a set of this work. On the last pages of Volume XL VI we found an article on Upsala; on the first pages of Volume XLVII, one on Ural-Altaic Languages, but not a word about Uqbar.

There's something manageable about the reproductions and challenges posed by these pieces by Duchamp and others. Compared to the current AI swamp we all invite into our phones, even its most consciously anti-human provocations are traceable enough to allow meaning, challenge, refutation. The visual language of AI, meaningwhile, is the culmination of productive forces predating and involved in its inception. There is an eternal glossiness to much of this art that serves as a too easy metaphor: there is in some sense nothing to object to in the typical AI product outside of the realms of engineering and accounting.

Which is perhaps why I spend so much time in Borges these days. That sense of "abominable" replication, its ability to overwrite this world.

The layered noise of Marnie Stern's vocal and guitar lines teases the idea that she is capable of this sort of overload. The furiously layered rhythms of Zach Hill's drumming on Stern's first three records sometimes gives the sense that the incursion has already happened.